Looking for Action

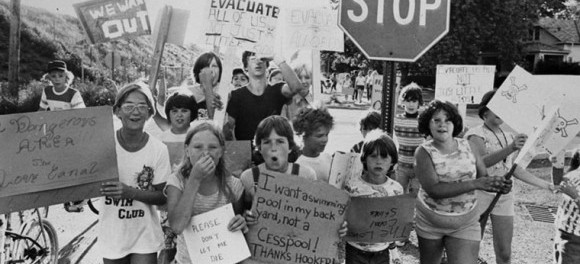

Local children in Niagara Falls, New York, protest toxic contamination of Love Canal, as seen in the documentary A Fierce Green Fire: The Battle for a Living Planet. Photo by the Buffalo Times-Courier, courtesy of the Butler Library at Buffalo State.

Local children in Niagara Falls, New York, protest toxic contamination of Love Canal, as seen in the documentary A Fierce Green Fire: The Battle for a Living Planet. Photo by the Buffalo Times-Courier, courtesy of the Butler Library at Buffalo State.

Love Canal became a national crisis in 1978 when rusting metal drums poked through the surface of an elementary school playground built on a former industrial dump site. The toxic petrochemical wastes eventually began leaching into the backyards and basements of homes in the neighborhood. It quickly became a not-so-shining example of a community contaminated by a multinational corporation unencumbered by government regulations.

Sherry Cable, professor of sociology, is studying how corporations are treating the industrial communities they inhabit and how the municipalities are dealing with community safety and environmental health. Her current focus is on the oil and gas industry’s use of a controversial technique called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking.

Fracking employs an unconventional horizontal drilling method to extract previously unobtainable natural gas and oil from shale rock. It involves pumping water, chemicals, and sand into a well under high pressure to open channels in the rock and force out the oil or gas. Although it has revitalized the industry in the United States, fracking may be causing some unintended environmental consequences.

“With Love Canal, it took over thirty years for the chemicals to migrate, reach the population, and then for the population to show symptoms,” Cable said. She is worried the long-term effects of fracking could result in a similar scenario of inadequate regulation at all government levels until somebody gets sick.

Another area of concern for Cable is that oil and gas companies are receiving exemptions from key federal environmental laws such as the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act. For example, in 2011, Congress amended the 2005 Energy Policy Act to make fracking operations exempt from the Safe Drinking Water Act.

In graduate school, Cable studied citizen mobilization following the partial meltdown at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear reactor. “Residents pushed and made noise until the federal government finally agreed to hold public hearings on the accident,” Cable said. “Long story short, the nuclear regulatory system was overhauled and new regulations were adopted. The commercial nuclear power industry pretty much died out in the US.”

Today her research is centered about 500 miles southwest of Love Canal, in her home state of Ohio—an area already exploited by coal mining.

The New Gold Rush

According to Cable, fracking on public land in the Ohio River Valley has caused what some refer to as “the new gold rush.” Working wells were built so quickly, regulation, by default, fell to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, even though existing regulations covered only conventional mining and drilling techniques.

“The problem is the practice of fracking is way ahead of regulation, which varies from state to state because Congress said they weren’t touching the subject and left it up to the states,” Cable said. “The lack of a national policy on fracking has created a federal void in environmental authority over natural gas operations.”

As more and more fracking sites on public lands began dotting eastern Ohio, some municipalities tried to enact legislation to prevent, or at least regulate, the land grab. However, these efforts were dealt a serious blow in February 2015 when the Ohio Supreme Court decided the home rule amendment to the Ohio Constitution does not grant local governments the power to regulate oil and gas activities and operations within their city limits.

As an environmental sociologist, Cable is curious about the dynamics of the situation. “I wonder what the little guy does up against the corporations or government. Sometimes community residents band together and fight back, but most times they don’t. Why do people so often accept contamination or just kind of shrug it off or block it out so they are acting against their own interests?” Cable asked.

She believes people tend to accept the circumstances because powerful corporations are the source of jobs and revenues for governments of all levels. This is where Cable’s concept of trickle-down neoliberalism comes into play.

Rise of the Corporation

Neoliberalism is defined as “an approach to economics in which control of economic factors is shifted from the public sector to the private sector.” The notion became popular in the 1980s under then-president Ronald Reagan. It gave corporations increased standing in the public sphere, which eventually led to corporate values like privatization, fiscal austerity, and free trade becoming part of the public discourse.

“Corporations were able to bring about a cultural legitimization of corporate values—efficiency, profit maximization, scientific reasoning—all those values have become public ideology. The general population absorbed and accepted those values without question,” Cable said.

But what happens when the oil and gas industry comes to a city, small town, or village? Do village officials welcome drilling or resist it? Do citizens have a say about fracking in their communities? “If a company can assert its corporate values and influence on a state legislature, the effect on communities can be devastating,” Cable said. “This trickle down of neoliberalism hurts the communities.”

The power struggle between corporations and municipalities erupted way before the 1980s. Cable has traced it back to the landmark 1819 US Supreme Court decision in Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward. The court applied the contract clause of the US Constitution to private corporations, allowing Dartmouth College to continue as a private institution and limiting the power of the state to interfere with private charters.

Then, in 1886, the court used the Fourteenth Amendment to grant equal protection to corporations in Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Co. As ratified in 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment grants citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” and forbids states from denying any person “life, liberty or property without due process of law” or “the equal protection of the law.”

“They perverted the Fourteenth Amendment,” Cable claimed. “In fact, during the twenty-year period following that case, most of the cases before the Supreme Court that cited the Fourteenth Amendment by far had to do with business and not racial discrimination.”

As fracking spreads across the nation, the future of its regulation remains uncertain. With Congress taking a hands-off approach, individual states and communities are struggling to gather expertise and resources to deal with the onslaught. In the meantime, Cable will be keeping an eye on the little guys trying to prevent another environmental disaster like Love Canal.

Leave a comment